Teaching English in the Context of Pictorial Communication

Aleksander Schejbal

The main idea of the Animated Debate project is to facilitate intercultural

communication of young disadvantaged people through pictorial means.

The very choice of primarily non-verbal channels of communication discloses

an initial insight behind the creation of the workshops - the students

for whom the classes were organised had very limited knowledge of a

foreign language due to their various dysfunctions. They included many

different factors:

Psychological

(mental, emotional, behavioural)

Psychological

(mental, emotional, behavioural)

Physical

(impaired movement, sight, hearing)

Physical

(impaired movement, sight, hearing)

Social

(pathological family background, poverty, addiction)

Social

(pathological family background, poverty, addiction)

For the reasons listed above the majority of the students did not

acquire adequate education at school and could not or did not take

part in extra curricular language courses. With the exception of a

few participants this was a factor which hampered their ability to

take part in a verbal dialogue with their peers in other countries.

However, ability is not the only reason which had to be taken into

account. In order to enter a dialogue with a group of foreign students

a genuine interest and motivation is required. The obvious question

which comes up here - "what for?" is usually easier to answer in case

of students who can see the usefulness of such communication in terms

of their general knowledge, possible holidays abroad, future education

or employment. But what does such a dialogue mean for youngsters lacking

the most basic skills, with no prospects of travelling abroad in the

foreseeable future and slender chances of using a foreign language

in their everyday life?

Furthermore, foreign language teaching is an art governed by strict

rules. There are certain requirements for a well organised language

course, which are universally valid, the particular method used notwithstanding.

One of the key criteria is the nature of the group - its size, age

and the level of knowledge of the language being taught. If the group

is too large and the students are not well balanced in terms of their

language level, ability and age, the quality of the teaching is seriously

impaired and the results are discouraging both for the instructor and

the students. This is the situation faced by teachers working in therapeutic

or resocialization centres. The workshops organised there are usually

open to participants with various problems and dysfunctions who cannot

be selected according to specific requirements of a language course.

This was certainly the situation of the Animated Debate workshops in

all the four sites, where the basis for recruitment was not an English

test. This is also the most likely situation in other centres for dysfunctional

youth which might attempt to introduce foreign language teaching as

an element of their educational programme.

What follows is an attempt to find a practical solution to all these

key problems in designing an extra curricular language course for disadvantaged

youth. The problems had been foreseen before the Animated Debate project

started but some feasible ways to overcome them were only discovered

during the two-year language workshops taught in three different countries,

Poland, Romania and Italy. It is hoped that the observations gathered

by English language teachers working in the three different settings

and using different methods can be of some value in other educational

programmes teaching foreign languages to dysfunctional youth.

Team Building

Students of different ages, language abilities and level cannot constitute

a group for a properly organised English course. However, they can

form a team if they are faced with a task of a different nature involving

their various skills and interests and requiring mutual support and

cooperation. In case of the Animated Debate project this task consisted

in making a set of digital animations on topics voted as interesting

by the majority of workshop participants. A computerised workshop environment

is one of the easiest means of raising young people's motivation and

willingness to take part in an educational initiative. In addition,

the prospect of creating their own multimedia artwork is a clear incentive

to minds submerged in modern visual culture dominated by advertising,

video clips and computer games. For most of the students, so far only

passive consumers of digital pop art, the workshops were the first

opportunity to be creative in this field. Faced with such a challenge,

even the students with little interest in any of the topics suggested

for the animations readily joined the project.

The next step was to assign specific tasks to each of the participants

corresponding to their abilities and talents. The arts instructors

planned the classes in such a way that the students could move from

one task to another and participate in all the aspects of the cartoon

production. Obviously, some of the students could easily progress to

more advanced assignments, while the others could only master simpler

things at each stage. For example, some could go straight to animating

objects on the computer, while others could only draw simple shapes

in Paint or just make some paintings using traditional paintbrush techniques.

The main objective was to create a sense of team work with all the

participants learning new things needed to assure progress on the film

and each contributing their own ideas and artwork to the final creation.

The team building was assured by a different strategy used in the second

round of the workshops. Instead of choosing one film for the whole

group in the beginning, the students were first subdivided into smaller

teams working on the same topic but using different techniques and

styles. This proved a more manageable option in case of groups with

a large percentage of severely handicapped persons who needed help

from their friends. Working in a small group with no need of rotation

from one desk to another was easier for those kids, although the scheme

was more challenging for the instructors who had to monitor work on

different animations at the same time and adjust the syllabus to each

sub-teams.

The general scheme described above provided a context for language

teaching as an integral element of the workshops. Each of the Polish

groups worked on the same topic chosen for the animations in pair with

a partner group in another European country, Britain, Italy or Romania.

On both sides, the students could realise that there was a parallel

effort being undertaken to create a set of animations. This gave reason

to curiosity and interest in the creative process going on in a faraway

location. The project website provided space for all the groups to

publish the results of their progress (Animations Studio) before the

final results could be seen (Presentations). The pictorial exchange

effectuated through the website, taking various forms of drawings,

sketches, animations, provisional and chaotic as it might seem, was

taken as an invitation to a verbal dialogue. Some of the pictures in

order to convey meaning had to be accompanied by simple phrases; in

some cases the pictures were arranged as puzzles requiring the understanding

of a few English words to solve; for some animations a few words of

introduction were required. What could be seen on the website also

encouraged the students to send short e-mail messages to their partners

including simple individual or group introductions and more specific

questions relating to the artwork published. In short, the students

were willing to learn some language as a useful means to set up a communication

platform with their partners in another country. This willingness to

communicate with real people, working on the same subject was always

in the forefront of the English part of the workshops. The instructors

could not and did not prepare a syllabus for the whole course in advance.

Instead, they had to prepare each lesson individually to assure its

relevance for real communication tasks emerging in course of the pictorial

exchange. What follows is an illustration of the teaching process based

on the debate run by the partner workshop groups.

Teaching Vocabulary

The Polish-Italian partnership chose the ancient myth of Hercules

as the subject of the debate in the second round of the workshops.

This topic had a particular relevance for the Sicilian location of

one of the teams and the lively character of the main hero attracted

also the Polish students to the myth. The twelve labours of Hercules

provided a framework for the animation classes and created ample opportunities

for English language teaching. The language lessons closely followed

the progress of the arts workshops. Just as the students began with

easy tasks of learning how to create simple colourful shapes in Paint,

the English lessons introduced basic vocabulary connected with the

artwork produced.

In order to illustrate the vocabulary teaching methodology with concrete

examples we decided to choose a set of two initial introductory lessons

dealing with colours and parts of the body. Each student completed

the arts section of the workshops with a digital painting of Hercules,

a provisional outline of the main hero of the myth. They were asked

to print the pictures in colour and bring them to the language class.

The students had at their disposal paints, paintbrushes, crayons, sheets

of paper and digital dictionaries on computers- a usual set of tools

for the Animated Debate English workshops. These basic materials and

equipment were used in the language classes outlined as follows:

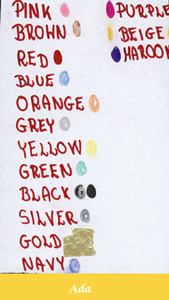

Lesson 1 - Colours

The

students were seated at one large desk and invited to present their

pictures of Hercules. Very different characters surfaced in the

pictures.

The

students were seated at one large desk and invited to present their

pictures of Hercules. Very different characters surfaced in the

pictures.

The

teacher directed the students' attention to different colours used

to depict Hercules. Some students attempted a realistic presentation

of the hero while others ventured more imaginative colourful depiction.

The

teacher directed the students' attention to different colours used

to depict Hercules. Some students attempted a realistic presentation

of the hero while others ventured more imaginative colourful depiction.

The

teacher suggested making a palette of all the colours used in the pictures.

This was done individually by each student using paintbrushes

to paint colourful shapes on paper.

The

teacher suggested making a palette of all the colours used in the pictures.

This was done individually by each student using paintbrushes

to paint colourful shapes on paper.

The

students were asked if they can name some of the colours in English.

The teacher was writing the names on the board as the students were

contributing new words. The list was then supplemented by the teacher

to cover all the colours painted on paper.

The

students were asked if they can name some of the colours in English.

The teacher was writing the names on the board as the students were

contributing new words. The list was then supplemented by the teacher

to cover all the colours painted on paper.

The

pronunciation of the words was drilled chorally and the meaning consolidated

by individual students coming to the board and underlying

each word with a corresponding coloured marker.

The

pronunciation of the words was drilled chorally and the meaning consolidated

by individual students coming to the board and underlying

each word with a corresponding coloured marker.

The

completed list was repeated chorally again and the students were asked

to write down the words next to corresponding colours on their

sheets of paper.

The

completed list was repeated chorally again and the students were asked

to write down the words next to corresponding colours on their

sheets of paper.

The

vocabulary was consolidated through a round the table circle of questions

and answers. Each student asked the pupil next to him/her

at the table the question "What colour?" and pointed at a part of the

picture. The question was answered by giving the right name and repeated

for the next student to answer.

The

vocabulary was consolidated through a round the table circle of questions

and answers. Each student asked the pupil next to him/her

at the table the question "What colour?" and pointed at a part of the

picture. The question was answered by giving the right name and repeated

for the next student to answer.

The

students took their palettes home to consolidate the vocabulary. Their

class work and homework at the same time looked similar to the

example shown above (Natalie's palette).

The

students took their palettes home to consolidate the vocabulary. Their

class work and homework at the same time looked similar to the

example shown above (Natalie's palette).

Lesson 2 - Parts of the Body

The lesson was prepared as a follow-up after the above. Its purpose

was to consolidate the colours, introduce new vocabulary relating to

parts of the body, as well as extend the functional language. This

is the outline of the lesson plan:

The

students had with them their pictures of Hercules and the previous

lesson colour notes.

The

students had with them their pictures of Hercules and the previous

lesson colour notes.

One

of the students was asked to come to the board and sketch his/her hero

in black.

One

of the students was asked to come to the board and sketch his/her hero

in black.

The

teacher asked the students to name parts of the body seen in the picture.

The words were written on the board by the teacher and

the missing names supplemented.

The

teacher asked the students to name parts of the body seen in the picture.

The words were written on the board by the teacher and

the missing names supplemented.

All

the words were drilled chorally by the class to consolidate the pronunciation.

All

the words were drilled chorally by the class to consolidate the pronunciation.

Each

student made notes on his/her picture of Hercules using arrows to connect

words and parts of the body.

Each

student made notes on his/her picture of Hercules using arrows to connect

words and parts of the body.

Before

practising simple dialogues based on the vocabulary introduced, the

class consolidated the colour words from the previous lesson.

Before

practising simple dialogues based on the vocabulary introduced, the

class consolidated the colour words from the previous lesson.

A

new question "What colour is his head/neck/leg, etc?" was introduced

and repeated chorally?

A

new question "What colour is his head/neck/leg, etc?" was introduced

and repeated chorally?

The

question was practised round the table with individual students pointing

at a part of the picture next to him/her and eliciting the

name of the proper colour.

The

question was practised round the table with individual students pointing

at a part of the picture next to him/her and eliciting the

name of the proper colour.

The

students took their annotated pictures home to consolidate both the

vocabulary and the function practised.

The

students took their annotated pictures home to consolidate both the

vocabulary and the function practised.

Both the lessons involved the majority of the workshop participants

whose language level was rather low. Some of the students refused to

participate in the classes, either due to a higher level of English

or a lack of interest in this kind of activity. They were assigned

complementary tasks on the computer. The sketches of Hercules included

some items not covered in the lessons, like weapons, clothes or background

details. The extra task assigned consisted in making a list of these

things and translating them into English using a digital dictionary.

This vocabulary was then integrated into the main class with the outsider-students

asking the colour questions with a broader range of words while the

rest of the class was listening and practising comprehension skills.

Teaching functions

From the very beginning the students were taught functional language

useful in the context of the "debate". Before moving to more conceptual

acquisition of basic grammar points the students learned how to enter

simple exchanges based on the artwork they were making in course of

the animation classes. In order to illustrate the methodology at this

stage we have chosen a part of the Hercules storyboard made to provide

a basis for the animated film. The students are already quite advanced

in their work on the film having created the scenario and the main

characters as well as outlined the whole story in pictorial terms.

The English lessons closely followed the progress of the animation

workshops. Two of the lessons taught illustrate this interconnection.

Lesson 1 - Expressing ability

The picture shows Hercules on his way to Nereus. He is surrounded

by snakes and stones in the desert. The figures were made of plasticine

and put on painted cardboard. The consecutive positions of the figures

were then photographed with the digital camera and the phases edited

on the computer for the final animation. The original cardboard stage

was used for the English class. The lesson was outlined as follows:

The

students were seated around their arts workshop table with the cardboard

stage in the middle and the whole scene visible to everybody.

The

students were seated around their arts workshop table with the cardboard

stage in the middle and the whole scene visible to everybody.

The

scene noun vocabulary was revised in a set of questions: What's this?

Is it a stone? What colour is the cactus?, etc.

The

scene noun vocabulary was revised in a set of questions: What's this?

Is it a stone? What colour is the cactus?, etc.

The

teacher introduced new verbs needed to practise new functions in the

lesson: walk, crawl, raise, fight, jump and throw. Each of the

words was illustrated by showing the concrete actions on the scene.

The

teacher introduced new verbs needed to practise new functions in the

lesson: walk, crawl, raise, fight, jump and throw. Each of the

words was illustrated by showing the concrete actions on the scene.

The

key lesson question: Can Hercules walk/crawl, etc? was introduced and

consolidated chorally along with the movement illustration.

The

key lesson question: Can Hercules walk/crawl, etc? was introduced and

consolidated chorally along with the movement illustration.

Then

individual students were asking similar questions round the table eliciting

answers in words and movements on the cardboard stage.

Then

individual students were asking similar questions round the table eliciting

answers in words and movements on the cardboard stage.

The

structures learned and practised in the visual context were then applied

to real life situations in a set of questions/answers of the

type: Can you crawl? Yes, I can/ No, I can't.

The

structures learned and practised in the visual context were then applied

to real life situations in a set of questions/answers of the

type: Can you crawl? Yes, I can/ No, I can't.

A

more advanced application of the structure with the introduction of

the third person singular he/ she was then presented and practiced

thus allowing the teacher to consolidate a basic grammar point.

A

more advanced application of the structure with the introduction of

the third person singular he/ she was then presented and practiced

thus allowing the teacher to consolidate a basic grammar point.

Lesson 2 - Talking about numbers

The picture shows four scenes on the same storyboard with Hercules

and Nereus as the main characters. Again the stage was put on the table

in the middle of the group of students for everybody to be able to

see and move characters on the cardboard. In addition, students brought

with them various plasticine objects created for other film scenes

like snakes, arrows, apples, snails, etc. These visual resources provided

the tools for the presentation of new language material and consolidation

of the previous lesson structure:

The

class started with the revision of the can you/he/she...? structure.

This was done in a set of questions/answers referring to a new visual

context; a few new words were introduced to describe new objects on

stage.

The

class started with the revision of the can you/he/she...? structure.

This was done in a set of questions/answers referring to a new visual

context; a few new words were introduced to describe new objects on

stage.

The

teacher then introduced a new question relatively easy to master now:

Can you see a tree? Can you see a yellow tree?, etc and elicited

answers of the type: Yes, I can/ No, I can't. I can see a green tree.

This was partly a follow up to the previous functions and partly a

preparation to the main lesson point.

The

teacher then introduced a new question relatively easy to master now:

Can you see a tree? Can you see a yellow tree?, etc and elicited

answers of the type: Yes, I can/ No, I can't. I can see a green tree.

This was partly a follow up to the previous functions and partly a

preparation to the main lesson point.

Once

the students mastered the above in a round of questions/answers a more

challenging structure was presented: How many trees can you

see? The students repeated the question chorally a few times and then

practiced it round the table changing the objects referred to. They

already knew numbers needed to give answers to the questions.

Once

the students mastered the above in a round of questions/answers a more

challenging structure was presented: How many trees can you

see? The students repeated the question chorally a few times and then

practiced it round the table changing the objects referred to. They

already knew numbers needed to give answers to the questions.

The

group was subdivided into two teams. Each team had to reorganise the

stage adding new objects or removing some figures from the scene.

Then each student from the team had to ask at least one question for

the members of the other team to answer. The roles were then reversed.

The

group was subdivided into two teams. Each team had to reorganise the

stage adding new objects or removing some figures from the scene.

Then each student from the team had to ask at least one question for

the members of the other team to answer. The roles were then reversed.

The

lesson was concluded with some real life situations: How many computers

can you see?, Can you see a snail?

The

lesson was concluded with some real life situations: How many computers

can you see?, Can you see a snail?

These two consecutive lessons are just an extract from the syllabus.

Teaching functional language was essential for the task of introducing

the students to real exchanges with their foreign partners. Pictorial

resources published in course of the project on the website (Animations

Studio) by all the paired groups created curiosity in what was happening

in the partner workshops and provided incentive to asking questions.

Obviously, the teacher's support was needed to enter a genuine dialogue.

Sometimes it took the form of corrections of original questions; sometimes

slight additions were needed. For example, in reference to the above

lessons, most of the students could master questions like: Can your

Hercules walk/ run/ talk, etc? and email them to their partners. The

teacher's addition would then be: Can your Hercules run like ours can?

See it at … (website link). In some cases the teacher's contribution

had to go far beyond the students' capacity. Especially in cases where

some key messages had to be translated for the students to mail them

to their partners or in case of received messages written in the language

beyond the students' ability. The main effort was to keep up the "debate"

even in spite of serious language difficulties.

Teaching Grammar

Teaching grammar is usually the hardest part of language teaching

to teenagers if done for "its own sake" without any stimulating context.

Certainly, this task was facilitated here by the main methodological

principle of introducing all language items in close interconnection

with pictorial assignments in which the students were involved. How

elementary grammar points were presented, practiced and consolidated

is shown by the following extracts from the syllabus:

Lesson 1 - Present Continuous

|

|

The present continuous tense was introduced in course of the students

working on the above scene of Hercules visiting the king. All the detailed

items had already been created for this scene (plasticine figures like

in the top close-up), still more figures and storyboards were missing

for the following ones. In order to make a stop-frame animation of

the whole scene each of the movements had to be actually made against

the background, consecutive positions of the figures photographed with

the digital camera and the whole sequence edited on the computer. This

was a task requiring diligence, patience and a relatively slower pace

of workshops at this stage. The students worked in two groups at two

distant corners of the classroom. One team was animating the scene

(shots made with digital camera and edited on the computer) while the

other was finishing some details for the next storyboard using traditional

arts techniques (moulding, drawing, painting). Two instructors were

running the workshops with two computers available at the two desks.

The English lesson was taught within the four-hour workshop and divided

into three parts:

Presentation of new grammar point (around 30 minutes in the beginning

of workshop)

All

the students were gathered at one table for this part of the lesson.

The teacher started with the revision of verbs describing students'

tasks in the classroom (paint, draw, take photographs, etc) followed

by introduction of a few new verbs.

All

the students were gathered at one table for this part of the lesson.

The teacher started with the revision of verbs describing students'

tasks in the classroom (paint, draw, take photographs, etc) followed

by introduction of a few new verbs.

A

new structure was introduced with the question: What are you doing,

Kate - walking, painting, sitting? The form of the question made it

relatively easy to elicit "sitting" in this case. Similar questions

were asked round the table with students giving answers prompted in

the questions.

A

new structure was introduced with the question: What are you doing,

Kate - walking, painting, sitting? The form of the question made it

relatively easy to elicit "sitting" in this case. Similar questions

were asked round the table with students giving answers prompted in

the questions.

The

students were asked to fetch some plasticine figures from their arts

workshop table. This helped the teacher to introduce the third

person in questions referring to the figures like in the following

examples: What is Hercules doing? Is he talking to the king? or What

are the nymphs doing? Are they swimming? The students could easily

understand the questions, still they found it difficult to make full

answers like Yes, he is talking to the king. No, they aren't swimming.

The

students were asked to fetch some plasticine figures from their arts

workshop table. This helped the teacher to introduce the third

person in questions referring to the figures like in the following

examples: What is Hercules doing? Is he talking to the king? or What

are the nymphs doing? Are they swimming? The students could easily

understand the questions, still they found it difficult to make full

answers like Yes, he is talking to the king. No, they aren't swimming.

To

clarify the difficulty the full conjugation was written on the board

in a sufficient number of examples for the students to understand.

They had already been acquainted with the conjugation of the verb "to

be" so the present task was relatively easy.

To

clarify the difficulty the full conjugation was written on the board

in a sufficient number of examples for the students to understand.

They had already been acquainted with the conjugation of the verb "to

be" so the present task was relatively easy.

This

part of the lesson was concluded with the students themselves asking

their own questions round the table.

This

part of the lesson was concluded with the students themselves asking

their own questions round the table.

Practice (around 40 minutes in the middle of the workshop)

This

was integrated with the students' actual work on the film. The two

groups were asked to stay at their two distant workshop tables.

The teacher showed them how they could communicate with each other

using the Intranet computer network with the simplest Windows pop-up

option.

This

was integrated with the students' actual work on the film. The two

groups were asked to stay at their two distant workshop tables.

The teacher showed them how they could communicate with each other

using the Intranet computer network with the simplest Windows pop-up

option.

Each

group was given the task of finding out what the other group was doing

and report the findings to the teacher using only computers

for this purpose.

Each

group was given the task of finding out what the other group was doing

and report the findings to the teacher using only computers

for this purpose.

In

order to do this they had to write questions like "What are you doing?"

"Is Hercules fighting the dragon?" "Are you painting the tree?"

which would pop-up on their partners screen. The answers were sent

back in the same way. The students could use on-line dictionaries to

look up new words for more advanced questions.

In

order to do this they had to write questions like "What are you doing?"

"Is Hercules fighting the dragon?" "Are you painting the tree?"

which would pop-up on their partners screen. The answers were sent

back in the same way. The students could use on-line dictionaries to

look up new words for more advanced questions.

The

concluding reports took similar forms as both the groups had to sent

their findings to the teacher's computer.

The

concluding reports took similar forms as both the groups had to sent

their findings to the teacher's computer.

The

on-line exchange proved quite exciting to everybody. It both allowed

the students to make a break in the long animation workshop

and practice a new grammar structure in writing.

The

on-line exchange proved quite exciting to everybody. It both allowed

the students to make a break in the long animation workshop

and practice a new grammar structure in writing.

Consolidation (around 20 minutes at the end of workshop)

Consolidation

was done orally with all the students sitting at one table again. They

were shown parts of their own animations on the computer

screen which was also a suitable conclusion for the arts workshop.

Consolidation

was done orally with all the students sitting at one table again. They

were shown parts of their own animations on the computer

screen which was also a suitable conclusion for the arts workshop.

The

students were asked to make comments on the actual movements on the

screen. They were either coming up with comments themselves

like "Oh, the dragon is coming!" or were answering questions like "Who

is talking to Hercules?", "Is he standing or walking?"

The

students were asked to make comments on the actual movements on the

screen. They were either coming up with comments themselves

like "Oh, the dragon is coming!" or were answering questions like "Who

is talking to Hercules?", "Is he standing or walking?"

In

cases of difficulty or inaccuracy the relevant movements were played

again and correct comments elicited.

In

cases of difficulty or inaccuracy the relevant movements were played

again and correct comments elicited.

The

new structure was revised in subsequent lessons as was the case with

all the key points of the syllabus.

The

new structure was revised in subsequent lessons as was the case with

all the key points of the syllabus.

Lesson 2 - Prepositions of place and position

This lesson was based on a scene rich with visual content - the picture

presents the meeting of Atlas with the nymphs and the dragon behind

them. The plasticine figures are easily moved against the painted cardboard

background and new objects can be introduced on stage. The English

lesson was organised as follows:

The

class was seated around one table with the stage set in the middle.

Each student had with them a few other plasticine objects or

characters used in other scenes of the film.

The

class was seated around one table with the stage set in the middle.

Each student had with them a few other plasticine objects or

characters used in other scenes of the film.

The

teacher introduced basic prepositions of place and position including

in, on, near, between, under, over, in front of, behind and into by

moving Atlas around the scene and commenting on his position. The students

were asked to repeat the prepositions chorally once everybody grasped

the relevant meaning in each case.

The

teacher introduced basic prepositions of place and position including

in, on, near, between, under, over, in front of, behind and into by

moving Atlas around the scene and commenting on his position. The students

were asked to repeat the prepositions chorally once everybody grasped

the relevant meaning in each case.

The

prepositions were consolidated on the basis of visual demonstration

on the scene in a set of teacher questions and elicited student answers:

Where is the dragon? In front of the nymphs or behind them? The expected

answer "behind" was usually forthcoming. In case of mistakes, the meaning

of the preposition was presented again with the help of visual resources.

The

prepositions were consolidated on the basis of visual demonstration

on the scene in a set of teacher questions and elicited student answers:

Where is the dragon? In front of the nymphs or behind them? The expected

answer "behind" was usually forthcoming. In case of mistakes, the meaning

of the preposition was presented again with the help of visual resources.

The

students practised the new vocabulary in pairs asking the same type

of question: Where is x? In front of y? with or without the prompt

this time.

The

students practised the new vocabulary in pairs asking the same type

of question: Where is x? In front of y? with or without the prompt

this time.

At

the end of the lesson the revision of the whole material was connected

with the repetition of the imperative structure previously introduced.

The students were asked to put their own plasticine figures on stage

following the teacher's instructions like: Kasia, put your snail near

the dragon! Now move it slowly into his mouth, etc. Most of the students

could understand the directions and followed them gladly.

At

the end of the lesson the revision of the whole material was connected

with the repetition of the imperative structure previously introduced.

The students were asked to put their own plasticine figures on stage

following the teacher's instructions like: Kasia, put your snail near

the dragon! Now move it slowly into his mouth, etc. Most of the students

could understand the directions and followed them gladly.

The above lessons illustrate the key concept of grammar teaching in

the context of the Animated Debate classes. All the language points

were closely interconnected with the pictorial resources contributed

by the students and playing a distinct role in the whole process of

film making. Accordingly, the visual context enhanced the acquisition

of more conceptual language items. On the other hand the students could

see the value of the new structures learnt while engaging in simple

exchanges in English with their partner group working on the same theme

in another country. The next chapter looks more closely into the ways

in which this debate in a foreign language was effectuated.

Communication Platform

The Animated Debate workshops ran for two years. Two different communicative

strategies were applied and tested in each of them. Accordingly, the

presentation of the students' communication in English is divided into

two parts.

Year 2003/2004

In the first year of the workshops English exchanges between partner

groups were effectuated through a discussion forum called the Animated

Debate Junior Common Room. The basic idea behind the creation of this

message board was to engage the students into a regular dialogue with

their partners alongside the pictorial exchanges which were the main

means of communication in the "animated debate". The partner group

instructors agreed on a syllabus to follow with each group to make

the exchanges consistent while leaving space for topics emerging in

the course of the arts workshops. In principle, the English course,

with its methodology outlined above, was structured in such a way as

to facilitate the student debate with its two main assignments.

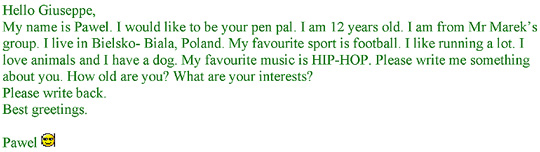

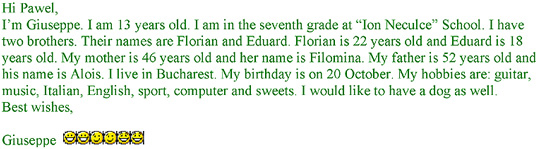

Student Introductions

The above examples show what the students were able to write to introduce

themselves to their partners. Such posts published in the Junior Common

Room were results of a series of English lessons based on example introductions

taken from books and the Internet and integrated with the basic language

course. The students had to read and understand this sort of texts

before moving on to a more challenging task of writing their own introductions

with the teacher's help. The following problems surfaced in the course

of this part of the syllabus:

Participants

of the workshops were at different levels of English writing skills

and it was impossible to expect all the students to

write their profiles.

Participants

of the workshops were at different levels of English writing skills

and it was impossible to expect all the students to

write their profiles.

Partner

groups progressed at different speed and some students, having published

their introductions, had to wait a long time for their counterparts

to follow up.

Partner

groups progressed at different speed and some students, having published

their introductions, had to wait a long time for their counterparts

to follow up.

Introductions

published on the forum looked much alike in many cases which made the

whole section rather monotonous and the partner profiles

not as interesting as could have been expected in the beginning.

Introductions

published on the forum looked much alike in many cases which made the

whole section rather monotonous and the partner profiles

not as interesting as could have been expected in the beginning.

The next part of the debate was planned for more lively and spontaneous

exchanges. The students had already been quite advanced in their work

on animations and thus curious of how the work was progressing in the

partner group.

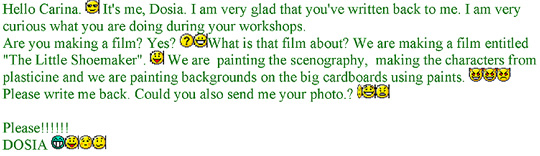

Student Open Debate

Once the students got to know each other they started asking questions

both of general nature and specific questions relating to the partner

workshops. As the sample post above shows, certain language items could

be practically applied in course of these exchanges. In this case the

message was written in a follow up to the present continuous tense

lesson. The students worked in pairs writing the messages off-line

on the computers while the teacher was moving from one desk to another

helping with new words and difficult structures. At the end of the

lesson (or a series of lessons in case of longer texts) the students

were able to log in the Junior Common Room, post their messages themselves

and read posts from other groups. This approach brought the following

problems:

The

questions which the students were eager to ask were much above their

foreign language ability. Substantial teacher contribution was

needed to keep the debate relevant to the actual students' queries.

It was difficult to maintain a balance between teaching and translating

and the problem was aggravated by different approaches chosen in each

site - this resulted in a certain inconsistency on the forum between

questions (e.g. longer letters partly translated for the students to

send) and answers (e.g. short, simple sentences sometimes written in

flawed language by students themselves).

The

questions which the students were eager to ask were much above their

foreign language ability. Substantial teacher contribution was

needed to keep the debate relevant to the actual students' queries.

It was difficult to maintain a balance between teaching and translating

and the problem was aggravated by different approaches chosen in each

site - this resulted in a certain inconsistency on the forum between

questions (e.g. longer letters partly translated for the students to

send) and answers (e.g. short, simple sentences sometimes written in

flawed language by students themselves).

Due

to different levels of English skills and the nature of disabilities

of the partner groups it was impossible to apply the same syllabus

in each workshop. Accordingly, a letter written at a certain language

level (e.g. including present continuous questions as the example above)

could not be properly answered by the partner group not knowing the

structure yet.

Due

to different levels of English skills and the nature of disabilities

of the partner groups it was impossible to apply the same syllabus

in each workshop. Accordingly, a letter written at a certain language

level (e.g. including present continuous questions as the example above)

could not be properly answered by the partner group not knowing the

structure yet.

The

above problems resulted in a certain discouragement both on the student

and teacher part. Although the debate was maintained until

the end of the first round of workshops each group concentrated more

and more on their own work and enjoyed the picture and animations exchange

much more than the debate in English.

The

above problems resulted in a certain discouragement both on the student

and teacher part. Although the debate was maintained until

the end of the first round of workshops each group concentrated more

and more on their own work and enjoyed the picture and animations exchange

much more than the debate in English.

One way of resolving the difficulties was to engage the students in

a whole class-to-class debate on a theme connected with their current

animation project. The students exchanged parts of their artwork and

asked their partners for interpretation of their content. Such texts

were written on the basis of contributions from all the students, sometimes

with the most advanced students taking the lead and the teacher helping

with difficult grammar points, correcting mistakes or translating the

most difficult parts. This is an example illustrating this approach;

one of Polish groups is answering their English friends' guesses on

the film storyboard:

The communicative approach of the first round of workshops was one

of the key issues discussed between the partners during the summer

break. Taking into account the difficulties of separate verbal student

exchanges they decided to look for ways of closer interconnection of

pictures and words in the next round. What follows is an overview of

the second year methodology.

Year 2004/2005

The partners agreed that the students' communication in the second

round of workshops would entirely be based on pictorial exchanges.

Accordingly, English was taught in the context of work on the animations

and verbal messages accompanied artworks produced in course of film

making. The Junior Common Room discussion board was thus left inactive

for the whole year and the picture-word messages were either e-mailed

or published on the project website in one of the two sections accessible

to all the groups, Animation Studio or Presentations. In order to illustrate

the methodology applied to effectuate the student debate we have chosen

the following sample projects.

Picture/Animations Exchange

| KASIA |

|

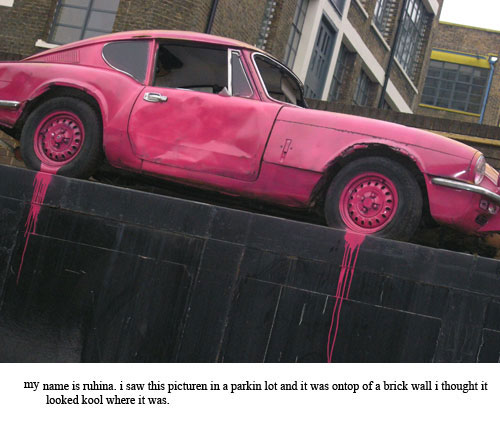

The above work is a sample of the interim stage of the English - Polish

exchange. Both groups were practising basic digital photography and

animation techniques while working on the topic of My Yard. The theme

was chosen as an opportunity for the students to introduce themselves

to their partners through visual presentation of their local environment.

The two groups worked in different arts techniques and the language

part was also integrated into the project differently. The Polish

group started with the verbal presentation of the concept of My Yard.

The students came up with a set of key ideas associated in their

mind with this concept. They were expressed either in simple words,

like in the above project made by a mentally disabled girl, or longer

phrases and sentences. The English teacher could easily adjust the

tasks to individual students' ability - following the lesson introducing

the relevant vocabulary, the students were helped to express their

ideas in a doc. format using on-line dictionaries. When this had

been done, the students proceeded to visual illustration of these

ideas, again practising drawing or animation techniques adjusted

to their ability. In the course of this work the list of English

words could be modified, supplemented, revised, etc. Once the project

was finished it was published on the AD website for the partner group

to view. The answer would sometimes appear in a very different style

and format which the picture shown below, contributed by a student

from London, illustrates.

The London students did not take part in the English course for a very

simple reason - without any additional classes they were much more

advanced in their English language skills than their foreign partners.

The workshops concentrated on digital arts. However, in order to

maintain communication with their Polish partners, the students sent

verbal messages as well. The above picture with a subtitle shows

how this was done. The group started work on the topic of My Yard

with taking digital photos on the spot. The material was then used

in the computer animation workshops but before the final results

were achieved, annotated pictures were sent to the partner group

and published on the AD website. This gave the Polish group an insight

into the Yard of their partners and an opportunity to read some English

comments in an authentic language, far from the model standard English.

Film Subtitles/Soundtrack

Once, there was a tree that loved a little boy. The boy came to the

tree every day.

He ate the fruit.

The boy played with the tree every day.

He climbed the tree trunk and swung on its branches.

The boy loved the tree. He loved it very much and the tree was happy.

The boy was growing up, he found a girlfriend and the tree was often

alone.

When the boy finally returned, he said: I need a house. Can you give

me a house? The tree answered: You can cut my branches and build a

house.

Time passed by. When the boy finally returned he said: I want to have

a boat to travel far away from here. Can you give me a boat? The tree

answered: You can cut my trunk and build a boat.

Many years passed before the boy came back. - I have nothing to give

you. I'm only an old stump - said the tree.

I don' t need too much. I'm just looking for a quiet place to sit down

and rest.

Each round of the workshops finished with the presentation of animated

films produced by the partner groups and made available for downloading

on the AD website. The animations were meaningful in themselves since

they were visual interpretations of the same theme chosen by each pair

of groups. However, some groups made an attempt to express the meaning

in words as well, either in the form of soundtrack dialogues or subtitles.

The above example taken from the Polish film "The Giving Tree" illustrates

what the students were able to achieve in this respect with the teacher's

assistance. The subtitles were written in the last phase of the workshops

and required the students to use all the language skills acquired so

far. The text was first written in Polish and then translated into

English; the task set for the whole group was an opportunity to revise

the key vocabulary, functions and structures taught during the course.

The translation was made in a series of English classes accompanying

the final edition of the film. Each class was divided into two parts:

first the students worked in pairs and using on-line dictionaries as

well as their notes from the course translated the key words appearing

in the text. Then, working in the whole group, they proposed their

versions of the English sentences. The sentences written on the board

were improved on the basis of suggestions and corrections contributed

by individual students. Only in the last stage of the process the teacher

proposed her additions and improvements. The agreed version of the

text was then used in the arts workshops which entered the final stage

of film editing.

Conclusions

The Animated Debate workshops proved the value of the main principle

of the project - visual narration is a viable way to connect dysfunctional

youth across borders and cultures. ICT can be used effectively to communicate

pictorial messages between groups coming from very different backgrounds

but in their everyday life equally disconnected from the mainstream

of societal development. Besides the value of intercultural communication,

such exchange provides a framework in which various educational initiatives

can be incorporated. The English workshops outlined above were an attempt

to prove the validity of foreign language teaching in this framework.

Certainly, the participants of the workshops could not progress in

their new language acquisition at the pace expected of a standard English

course. This was mainly due to two factors: their mental or behavioral

disabilities and the nature of groups not well balanced in terms of

the language level. None of the problems could be resolved in the short

term - the very fact that the students entered the course and most

of them were able to complete it was a success in itself. In spite

of these drawbacks most of the students could upgrade their knowledge

of the foreign language and see its practical relevance as a tool in

real communication. This was a totally new experience for the majority

of the course participants who had previously studied English only

as a school subject - an abstract theory in terms of real life. Now

they could exchange messages, simple as they were, with their peers

in other countries. This certainly raised their motivation for further

education. The key question which arose at the end of the workshops

was: when do the workshops start after holidays? The students perceived

the continuation of the course as something obvious which goes without

saying; the fact that this particular course had a limited life span

was far from being evident to them.

The students expectations could and should be met in a broader context.

The purpose of this publications is to reach a large group of educators

working with dysfunctional youth and give them guidelines and encouragement

to involve their students in an intercultural debate. The pilot workshops

for teachers organised in Bielsko-Biała, Poland brought very promising

results in this respect. The art of visual narration as a tool to connect

youth across cultures and borders was welcomed with interest and understanding

by the trained instructors. It is believed that the feasibility and

validity of foreign language teaching in the context of pictorial communication

was also seen.